For more on the book itself, visit the publisher’s website.

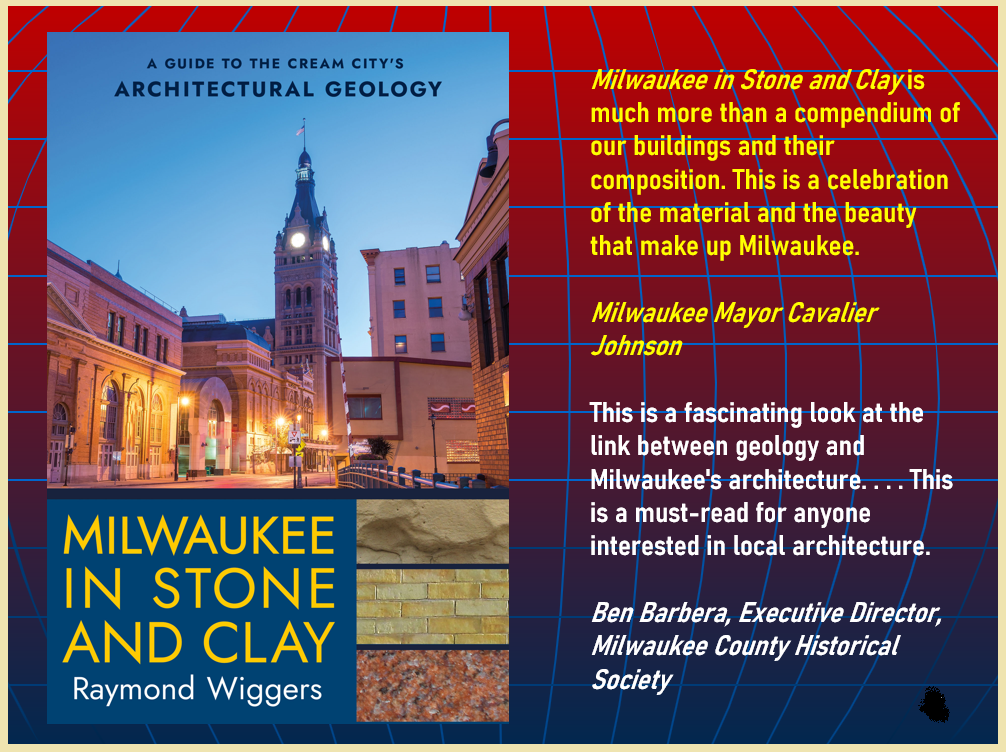

This page serves as a forum in which I provide updated and additional information germane to the content of my 2024 book, Milwaukee in Stone and Clay: A Guide to the Cream City’s Architectural Geology, henceforth abbreviated MSC.

Please keep in mind that there’s also a lot of additional supplementary material and images pertinent to MSC and Milwaukee architectural geology can be found at my Flickr account. It’s best accessed from my “Wiggers Museum of Natural History” page.

News on the Book (most recent events at top)

- August 4, 2024: Added an addendum to Item 4, below. It discusses the new, complete MKE Lifestyle interview available online.

- June 27, 2024. Just published: The online July issue of MKE Lifestyle magazine. It contains a “Fifteen Minutes With Ray Wiggers” interview, starting on page 18. It discusses MSC and its subject matter. See Item 4, below, concerning some problems with the way the interview was presented.

- June 2, 2024: Added my Lexicon of Building-Stone Names to this website. This section, originally intended as an appendix in my Stone and Clay Series books, is offered here as a free additional resource for readers.

- May 26, 2024: Updated my Lectures and Tours pages detailing MSC-related events I’m now offering.

- May 10, 2024: Boswell Books and Historic Milwaukee, Inc. co-hosted my virtual talk on MSC.

- Late February 2024: MSC is now available!

Updates, Errata, & Random Musings

Overview. Like its sister sciences, geology is constantly in the process of revision. This can be the bane of the natural-history writer, whose job it is to convey currently held scientific understandings and prevailing ideas in a way that will not seem too confusing or intimidating to the general public—but who also has the obligation to be as accurate as possible.

However, the information the author relays often changes somewhat over the years, as specialists conduct additional research that either confirms or overturns preexisting hypotheses and accepted assumptions. As the geologist Robert Folk wrote in his classic work on sedimentary petrology, “None of the statements herein are to be regarded as final; many ideas held valid as recently as two years ago are now known to be false. Such is the penalty of research.” Never was a wiser word written.

The following items, which range from corrected typos and scientific updates to additional commentary on already accurate information, should be of special interest to architectural docents and students. Check back for new entries periodically.

Item 1. A Meditation on the MCR. One of the most fascinating aspects of North America’s history is what happened to this continent about 1.1 Ga ago, very late in the Mesoproterozoic era. It was then that the Midcontinent Rift (MCR) formed. A titanic horseshoe-shaped breach in the crust, the MCR apparently extended from at least Oklahoma up through Minnesota, and back down through Michigan’s Lower Peninsula to Alabama.

While it is now buried far below the surface in most of its inferred range, the MCR is well exposed in the Lake Superior region. There we find vast quantities of mafic lava that erupted when the rift was young, as well as massive clastic sedimentary rock formations that were deposited after the eruptive phases had ended. It was from the latter that quarriers extracted Lake Superior Brownstone varieties for the building-stone trade (see Item 2, below),

For a science writer, this kind of dramatic and even cataclysmic event makes for catchy narrative. But it’s also a very slippery fish to get hold of. How exactly the MCR evolved, and what the timing of its various phases were, are still matters of intense debate among specialists. In MSC, I do discuss it a bit in chapter 2, but given the book’s limited permitted word count and its emphasis on architectural geology, I could only touch briefly on it later on with regard to the Mellen Gabbro, Isabella Anorthosite, and the Lake Superior Brownstones, which formed in association with it. (For example, see sites 5.7, 6.14, and 8.12). Here, however, I can go into a little more detail. And I’ll do so, step by step:

I. It’s generally thought that the rift was a product of a major episode of regional crustal extension. In other words, the continent’s midsection was stretched apart and thinned to the extent that deep-seated magma could rise to and erupt on the surface.

II. The interesting thing about this is that the late Mesoproterozoic was also the time of the Grenville Orogeny, one manifestation of the assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia. The Grenville was not just one mountain-building event, but a succession of at least three episodes that occurred hundreds of miles to what is now the east of the Lake Superior area. These pulses of continental compression were caused by the collision of ancestral North America (Laurentia) and various other landmasses.

III. Apparently the MCR formed in a time of extension between these compressional events. How exactly did that work? And there’s another nagging question: was the MCR just a passive rift, caused by mere crustal stretching, or was it also an active rift, fed by a mantle plume rising to the surface to form a hot spot? If it was only passive, why was so much lava—over 7 miles deep—erupted into it? On the other hand, wouldn’t it be an awfully big coincidence if this part of Laurentia had just happened to ride over an eruptive hot spot while there was passive rifting causing eruption, too? Needless to say, various researchers have proposed various models based on various types of evidence. No surprise there.

IV. After the rifting had ceased, layers of clastic sedimentary rocks (the Bayfield Group in Wisconsin and similar units in Minnesota; the Jacobsville Sandstone in Michigan) were deposited atop the lava deposits that occupied the down-dropped trench. I’ll have more to say about these Lake Superior Brownstones in Item 2, below.

V. But that’s not the end of it. At some point after 1.1 Ga ago, the great trench was inverted. In other words, this region experienced crustal compression that pushed the trench’s contents thousands of feet upward along reverse faults. (A great place to see this is Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, where one of those faults runs right up its spine.) It seems to make sense that this compression and inversion occurred during one or both of the final two Grenville phases (the Ottawan and the Rigolet). This, as I understand it, was the conclusion of a 2022 paper by Hodgin et al. (“Final inversion of the Midcontinent Rift during the Rigolet Phase of the Grenvillian Orogeny”). But some other MCR experts have averred that the inversion occurred not then, but long after the Grenville. Oy vey!

A wee glimpse of the Midcontinent Rift’s copious supply of basalt. This outcrop is on the northern Lake Superior shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula, at Esrey Park, near Eagle Harbor. It’s an extrusive mafic rock mapped as the Volcanic Member of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate. But local geologists call it the “Lake Shore Traps.” I will expound on the Swedish origin of “traps”‘ and “traprock” at some later time. © Raymond Wiggers

A wee glimpse of the Midcontinent Rift’s copious supply of basalt. This outcrop is on the northern Lake Superior shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula, at Esrey Park, near Eagle Harbor. It’s an extrusive mafic rock mapped as the Volcanic Member of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate. But local geologists call it the “Lake Shore Traps.” I will expound on the Swedish origin of “traps”‘ and “traprock” at some later time. © Raymond Wiggers

Item 2. A Meditation on the Lake Superior Brownstones. In MSC I describe several members of the Lake Superior Brownstone (LSB) family, including the “Portage Red” and “Raindrop” varieties of Michigan’s Jacobsville Sandstone, and Wisconsin’s Chequamegon Sandstone. See, for example. sites 5.14, 8.9. and 8. 12. Related to these is Minnesota’s Hinckley Sandstone, discussed at site 8.4.

In these accounts I note that for a long time geologists have been unsure of the age of the Chequamegon and Jacobsville formations—that estimates have ranged from very late in the Mesoproterozoic era, not long after the Midcontinent Rift formed, to the early Cambrian period, some 600 Ma later. And periodically I add that my own best guess is that they’re Neoproterozoic.

It turns out that my hunch was pretty good. In researching my third book of this series, Chicago Suburbs in Stone and Clay, I’ve come across a flurry of recent journal articles that report their teams’ latest geochronological analyses in the Midcontinent Rift area. Most of these have used the wondrous (wondrous to me, at least) detrital-zircon method, which establishes MDAs—maximum depositional ages—of LSB units.

Once the MDA of a rock unit is established, you know that it must be at least a smidgeon younger than that. After all, what you’ve actually determined is the age of the zircon crystals embedded in the sandstone. And those crystals originated somewhere else, at some earlier time. So what you still don’t know is how much younger than that the rock really is. If you’re lucky, you’ll find some other line of evidence that helps you with the lower age boundary. But if you don’t, all you can say is, “This unit is younger than XXX Ma.”

If you read the journal articles I cite above in chronological order, you’ll see there been a general trend from low-probability MDAs to those of a higher probability. I’m no geochronologist, but I assume this is a function of improving dating technology and improved experimental technique. Both the machines are the human beings are getting their act together, more and more.

I may have missed a report or two. If you think I have, please let me know. But from culling the numbers I’ve found so far, I have come up with these dates for the following LSB units:

Wisconsin’s Bayfield Group

- Orienta Sandstone: younger than 1059 Ma = 1.059 Ga = possibly super-late Mesoproterozoic, but more likely early Neoproterozoic.

- Chequamegon Sandstone: younger than 1035 Ma = 1,035 Ga = possibly super-late Mesoproterozoic, but more likely early Neoproterozoic.

Minnesota

- Hinckley Sandstone: younger than 1010 Ma = 1.01 Ga = possibly super-super-late Mesoproterozoic, but more likely early Neoproterozoic.

Michigan

- Jacobsville Sandstone: younger than 993 Ma; older than 986 Ma. = early Neoproterozoic.

For the Jacobsville, the lower boundary was taken from calcite-fill veins in Keweenaw Fault breccia, which were determined to post-date the sandstone formation. Pretty nifty, eh? But keep in mind that the MDA for the Jacobsville comes from its upper layers. So its bottom section, which was deposited earlier, is somewhat older.

At any rate, that’s what I’ve been able to cull from the literature so far. If you are a geologist who knows I’ve missed something, please let me know.

The Jacobsville Sandstone in its native habitat, along the Lake Superior shore, Presque Isle Park, Marquette, Michigan. Here it sits unconformably atop an Archean-eon rock mapped as “serpentinized peridotite.” In other words, it’s ultramafic rock more characteristic of the upper mantle than the crust, that was subsequently metamorphosed by contact with seawater. © Raymond Wiggers

The Jacobsville Sandstone in its native habitat, along the Lake Superior shore, Presque Isle Park, Marquette, Michigan. Here it sits unconformably atop an Archean-eon rock mapped as “serpentinized peridotite.” In other words, it’s ultramafic rock more characteristic of the upper mantle than the crust, that was subsequently metamorphosed by contact with seawater. © Raymond Wiggers

Item 3. And for all you Lake Superior Brownstone fans:

The correct pronunciation of the Chequamegon Sandstone is NOT shuh-KWA-muh-gun. It’s shuh-WAH-muh-gun.

Don’t ask me why. I don’t know. There is no logic to this. I just ask the locals.

But, while we’re at it, let’s have a preview of two stone types featured in my upcoming Chicago Suburbs in Stone and Clay:

Shawangunk Conglomerate (from New York State): pronounced SHON-gum.

Seisholtzville Granodiorite (from South Mountain, Pennsylvania): pronounced SEE-sholtz-vul.

Crossbedded Shu-WAH-muh-gun Sandstone used as ashlar on the Forest Home Cemetery Chapel, Milwaukee. Also note the beaded, color-coordinated mortar.© Raymond Wiggers

Crossbedded Shu-WAH-muh-gun Sandstone used as ashlar on the Forest Home Cemetery Chapel, Milwaukee. Also note the beaded, color-coordinated mortar.© Raymond Wiggers

Item 4. I was honored that MKE Lifestyle magazine considered MSC and me suitable grist for the interview mill in its July 2024 issue. I’d already been impressed at how much coverage the magazine gives to environmental and natural-history topics, issue after issue. The Cream City is lucky to have a general-readership publication that has that kind of editorial slant.

However, as I mentioned in my June 27th blog post, the interview as printed in an edited version online did put me in an embarrassing position and, given the kind of cuts that were made, has made me leery of participating in similar experiences in the future.

First, the accuracy issue. There is one photo caption in my interview spread that contains incorrect information that did not escape the attention of the magazine’s readership. Rest assured I did not write that text; nor was I asked to fact-check it. In the book trade, the author usually writes and later proofs the photo blurbs. But in the popular-periodical industry, captions are often done, usually without subsequent input by the interviewee, by a magazine staffer on a very tight deadline. In this case, I supplied the photos, but they were described by someone else.

So, for the record: the caption states that the red, Jacobsville-Sandstone-clad edifice shown was originally known as the Loyalty Building. Nope. It’s the Button Block, as clearly noted in MSC. The Loyalty is located one city block to the north. It, too. is covered in my book.

The caption also states that Milwaukee’s incomparable City Hall is made of both St. Louis Brick and Philadelphia Brick. Yes to St. Louis; nix to Philly. As also noted in MSC. To see the latter building material, pay a visit to the Milwaukee Club. And—you guessed it—that site is described in the book, too.

The other regret I have is how my interview answers—and one in particular—were edited. I’d been told beforehand that an abridged version of the interview would be used in the print version of MKE Lifestyle, but the digital version would feature the whole interview. Such was not actually the case. While the decision to cut or not to cut is solely the magazine’s, I was nevertheless saddened to see that the heart and soul of my final digital-version answer were surgically removed, apparently to give it a blander tone, and to make it more warm and fuzzy and “people-centered” rather than grandly geological. I’ve encountered this sort of fear of larger ideas and issues before.

At any rate, in order to restore the real flavor of what I was saying I here give the entire text of the final question and answer. The deleted sections are set in maroon.

- Any other highlights you’d like to add about MKE architecture and geology?

Just this. The underlying purpose of my book is to deepen or even transform the reader’s understanding of Milwaukee. I want the reader to see the city not just as a human construct, but also as a product of the unconscious will of nature itself.

No one who really studies the city’s built landscape can doubt that it’s a story of human genius, a lot of human sweat and muscle, and a remarkable amount of human planning and cooperation. I think of such designers as Edward Townsend Mix, Henry Koch, and the Eschweilers, who did so much to turn the muddy junction of three rivers into a world-class metropolis. I think of the foundrymen, canal-boat crews, and schooner sailors who managed to manufacture and transport massive prefab facade units twelve hundred water miles from New York City to the Iron Block on Wisconsin Avenue. And I think of Father Wilhelm Grutza, who built Milwaukee’s great St. Josaphat Basilica on a tight budget by shrewd bargaining and the savvy architectural recycling of building stone salvaged from two Chicago buildings.

That said, the city is also something else. It’s the planet Earth itself on public display. The whole city is an open-air museum of matter, energy, and geologic processes. Once you start exploring Milwaukee’s legacy of stone and clay, you’ll find yourself exploring one remote station of evolutionary time, and then another, and then another. You’ll see continents collide and ocean basins grow and shrink; you’ll see the advance and retreat of ice sheets, and the imprint of waves and tidal currents on the sediments they carried. As I’ve always said to my students: all it takes to open the door to unimagined worlds is to scratch below the level of the obvious. I hope my book will help Milwaukeeans do that.

Those excisions destroyed my chance to explain the central reason I wrote MSC and the other volumes of the Stone and Clay series. It was rather like cutting off the coda or grand summation at the end of a symphony. No composer would be happy with that.

One can say, certainly, that getting a portion of one’s message out is much better than not getting any of it out. Still, this experience of message-gutting and caption errors, embarrassing to me even if I wasn’t the culprit, has left me with a sense of both regret and wariness about how my words will be used by others.

*** ADDENDUM OF AUGUST 4, 2024 ***

I’m very happy to report that at some point subsequent to my posting the original version of this item, MKE Lifestyle did make the entire interview available online. I wasn’t made aware of this, and I just stumbled across it accidentally, but still, I’m grateful to the magazine for doing that.

Here’s the link to the full interview. Unfortunately, one of the photo captions—the one for City Hall—is still partially incorrect. The brick for that building did come from St. Louis, but not, I repeat not, Philadelphia.